These neural networks know what they’re doing

A certain type of artificial intelligence agent can learn the cause-and-effect basis of a navigation task during training.

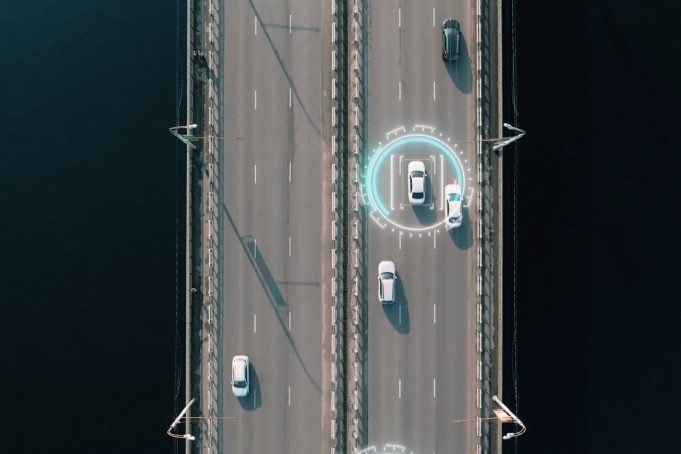

Neural networks can learn to solve all sorts of problems, from identifying cats in photographs to steering a self-driving car. But whether these powerful, pattern-recognizing algorithms actually understand the tasks they are performing remains an open question.

For example, a neural network tasked with keeping a self-driving car in its lane might learn to do so by watching the bushes at the side of the road, rather than learning to detect the lanes and focus on the road’s horizon.

Researchers at MIT have now shown that a certain type of neural network is able to learn the true cause-and-effect structure of the navigation task it is being trained to perform. Because these networks can understand the task directly from visual data, they should be more effective than other neural networks when navigating in a complex environment, like a location with dense trees or rapidly changing weather conditions.

In the future, this work could improve the reliability and trustworthiness of machine learning agents that are performing high-stakes tasks, like driving an autonomous vehicle on a busy highway.

“Because these brain-inspired machine-learning systems are able to perform reasoning in a causal way, we can know and point out how they function and make decisions. This is essential for safety-critical applications,” says co-lead author Ramin Hasani, a postdoc in the Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL).

Co-authors include electrical engineering and computer science graduate student and co-lead author Charles Vorbach; CSAIL PhD student Alexander Amini; Institute of Science and Technology Austria graduate student Mathias Lechner; and senior author Daniela Rus, the Andrew and Erna Viterbi Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science and director of CSAIL. The research will be presented at the 2021 Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) in December.

An attention-grabbing result

Neural networks are a method for doing machine learning in which the computer learns to complete a task through trial-and-error by analyzing many training examples. And “liquid” neural networks change their underlying equations to continuously adapt to new inputs.

The new research draws on previous work in which Hasani and others showed how a brain-inspired type of deep learning system called a Neural Circuit Policy (NCP), built by liquid neural network cells, is able to autonomously control a self-driving vehicle, with a network of only 19 control neurons.

The researchers observed that the NCPs performing a lane-keeping task kept their attention on the road’s horizon and borders when making a driving decision, the same way a human would (or should) while driving a car. Other neural networks they studied didn’t always focus on the road.

“That was a cool observation, but we didn’t quantify it. So, we wanted to find the mathematical principles of why and how these networks are able to capture the true causation of the data,” he says.

They found that, when an NCP is being trained to complete a task, the network learns to interact with the environment and account for interventions. In essence, the network recognizes if its output is being changed by a certain intervention, and then relates the cause and effect together.

During training, the network is run forward to generate an output, and then backward to correct for errors. The researchers observed that NCPs relate cause-and-effect during forward-mode and backward-mode, which enables the network to place very focused attention on the true causal structure of a task.

Hasani and his colleagues didn’t need to impose any additional constraints on the system or perform any special set up for the NCP to learn this causality — it emerged automatically during training.

Weathering environmental changes

They tested NCPs through a series of simulations in which autonomous drones performed navigation tasks. Each drone used inputs from a single camera to navigate.

The drones were tasked with traveling to a target object, chasing a moving target, or following a series of markers in varied environments, including a redwood forest and a neighborhood. They also traveled under different weather conditions, like clear skies, heavy rain, and fog.

The researchers found that the NCPs performed as well as the other networks on simpler tasks in good weather, but outperformed them all on the more challenging tasks, such as chasing a moving object through a rainstorm.

“We observed that NCPs are the only network that pay attention to the object of interest in different environments while completing the navigation task, wherever you test it, and in different lighting or environmental conditions. This is the only system that can do this casually and actually learn the behavior we intend the system to learn,” he says.

Their results show that the use of NCPs could also enable autonomous drones to navigate successfully in environments with changing conditions, like a sunny landscape that suddenly becomes foggy.

“Once the system learns what it is actually supposed to do, it can perform well in novel scenarios and environmental conditions it has never experienced. This is a big challenge of current machine learning systems that are not causal. We believe these results are very exciting, as they show how causality can emerge from the choice of a neural network,” he says.

In the future, the researchers want to explore the use of NCPs to build larger systems. Putting thousands or millions of networks together could enable them to tackle even more complicated tasks.

This research was supported by the United States Air Force Research Laboratory, the United States Air Force Artificial Intelligence Accelerator, and the Boeing Company.